I’ve participated in this year’s Google Summer of Code (GSoC)

program and have been working on the small (90h) “autopkgtests for the rsync

package” project at Debian.

Before you can start writing a proposal, you need to select an organization

you want to work with. Since many organizations participate in GSoC, I’ve

used the following criteria to narrow things down for me:

-

Programming language familiarity: For me only Python (preferably) as well

as shell and Go projects would have made sense. While learning another

programming language is cool, I wouldn’t be as effective and helpful to

the project as someone who is proficient in the language already.

-

Standing of the organization: Some of the organizations participating in

GSoC are well-known for the outstanding quality of the software they

produce. Debian is one of them, but so is e.g. the Django Foundation or

PostgreSQL. And my thinking was that the higher the quality of the

organization, the more there is to learn for me as a GSoC student.

-

Mentor interactions: Apart from the advantage you get from mentor

feedback when writing your proposal (more on that further below), it is

also helpful to gauge how responsive/helpful your potential mentor is

during the application phase. This is important since you will be working

together for a period of at least 2 months; if the mentor-student

communication doesn’t work, the GSoC project is going to be difficult.

-

Free and Open-Source Software (FOSS) communication platforms: I

generally believe that FOSS projects should be built on FOSS

infrastructure. I personally won’t run proprietary software

when I want to contribute to FOSS in my spare time.

-

Be a user of the project: As Eric S. Raymond has pointed out

in his seminal “The Cathedral and the Bazaar” 25 years ago

Every good work of software starts by scratching a developer’s personal

itch.

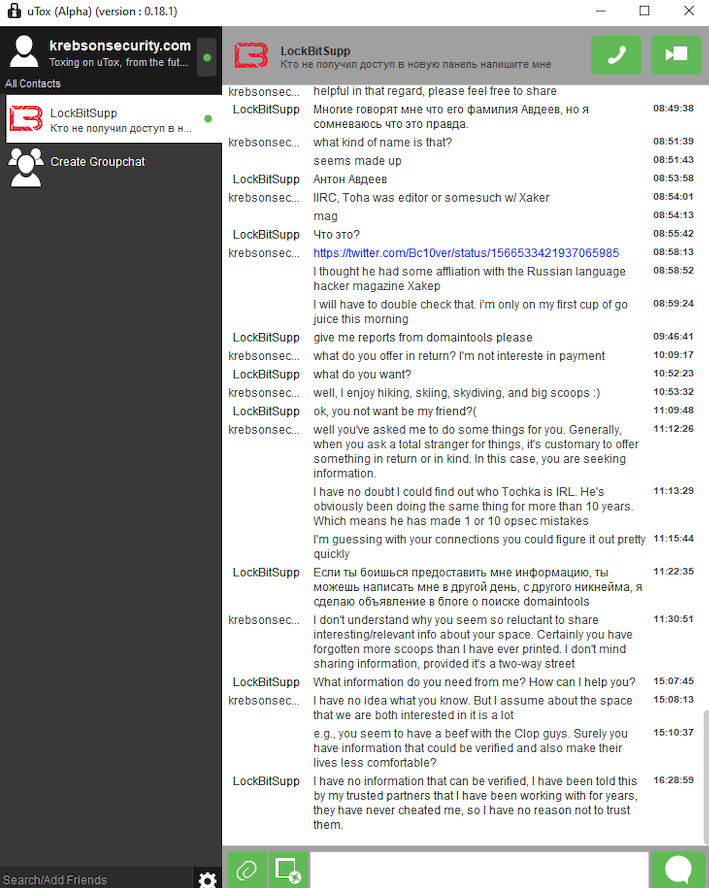

Once I had some organizations in mind whose projects I’d be interested in

working on, I started writing proposals for them. Turns out, I started

writing my proposals way too late: In the end I only managed to hand in a

single one … which is risky. Competition for the GSoC projects is fierce

and the more quality (!) proposals you send out, the better your chances are

at getting one. However, don’t write proposals for the sake of it: Reviewers

get way too many AI slop proposals already and you will not do yourself a

favor with a low-quality proposal. Take the time to read the

instructions/ideas/problem descriptions the project mentors have provided

and follow their guidelines. Don’t hesitate to reach out to project mentors:

In my case, I’ve asked Samuel Henrique a few clarification questions whereby

the following (email) discussion has helped me greatly in improving my

proposal. Once I’ve finalized my proposal draft, I’ve sent it to Samuel for

a review, which again led to some improvements to the final proposal

which I’ve uploaded to the GSoC program webpage.

Once you get the information that you’ve been accepted into the GSoC program

(don’t take it personally if you don’t make it; this was my second attempt

after not making the cut in 2024), get in touch with your prospective mentor

ASAP. Agree upon a communication channel and some response times. Put

yourself in the loop for project news and discussions whatever that means in

the context of your organization: In Debian’s case this boiled down to

subscribing to a bunch of mailing lists and IRC channels. Also make sure to

setup a functioning development environment if you haven’t done so for

writing the proposal already.

The by far most annoying part of GSoC for me. But since you don’t have a

choice if you want to get the stipend, you will need to signup for an

account at Payoneer.

In this iteration of GSoC all participants got a personalized link to open a

Payoneer account. When I tried to open an account by following this link, I

got an email after the registration and email verification that my

account is being blocked because Payoneer deems the email adress I gave a

temporary one. Well, the email in question is most certainly anything but

temporary, so I tried to get in touch with the Payoneer support - and ended

up in an LLM-infused kafkaesque support hell. Emails are answered by an LLM

which for me meant utterly off-topic replies and no help whatsoever. The

Payoneer website offers a real-time chat, but it is yet another instance of

a bullshit-spewing LLM bot. When I at last tried to call them (the

support lines are not listed on the Payoneer website but were provided by

the GSoC program), I kid you not, I was being told that their platform is

currently suffering from technical problems and was hung up on. Only thanks

to the swift and helpful support of the GSoC administrators (who get

priority support from Payoneer) I was able to setup a Payoneer account in

the end.

Apart from showing no respect to customers, Payoneer is also ripping them

off big time with fees (unless you get paid in USD). They charge you 2% for

currency conversions to EUR on top of the FX spread they take. What

worked for me to avoid all of those fees, was to open a USD account at Wise

and have Payoneer transfer my GSoC stipend in USD to that account. Then I

exchanged the USD to my local currency at Wise for significantly less than

Payoneer would have charged me. Also make sure to close your Payoneer

account after the end of GSoC to avoid their annual fee.

With all this prelude out of the way, I can finally get to the actual work

I’ve been doing over the course of my GSoC project.

The upstream rsync project generally sees little development. Nonetheless,

they released version 3.4.0 including some CVE fixes earlier

this year. Unfortunately, their changes broke the -H

flag. Now, Debian package maintainers need to apply those security fixes to

the package versions in the Debian repositories; and those are typically a

bit older. Which usually means that the patches cannot be applied as is but

will need some amendments by the Debian maintainers. For these cases it is

helpful to have autopkgtests defined, which check the package’s

functionality in an automated way upon every build.

The question then is, why should the tests not be written upstream such that

regressions are caught in the development rather than the distribution

process? There’s a lot to say on this question and it probably depends a lot

on the package at hand, but for rsync the main benefits are twofold:

- The upstream project mocks the ssh connection over which

rsync is most

typically used. Mocking is better than nothing but not the real thing. In

addition to being a more realisitic test scenario for the typical rsync

use case, involving an ssh server in the test would automatically extend

the overall resilience of Debian packages as now new versions of the

openssh-server package in Debian benefit from the test cases in the

rsync reverse dependency.

- The upstream

rsync test framework is somewhat idiosyncratic and

difficult to port to reimplementations of rsync. Given that the

original rsync upstream sees little development, an extensive test suit

further downstream can serve as a threshold for drop-in replacements for

rsync.

At the start of the project, the Debian rsync package was just running (a

part of) the upstream tests as autopkgtests. The relevant snippet from the

build log for the rsync_3.4.1+ds1-3 package reads:

114s ------------------------------------------------------------

114s ----- overall results:

114s 36 passed

114s 7 skipped

Samuel and I agreed that it would be a good first milestone to make the

skipped tests run. Afterwards, I should write some rsync test cases for

“local” calls, i.e. without an ssh connection, effectively using rsync as

a more powerful cp. And once that was done, I should extend the tests such

that they run over an active ssh connection.

With these milestones, I went to work.

Running the seven skipped upstream tests turned out to be fairly

straightforward:

- Two upstream tests concern access control lists and extended

filesystem attributes. For these tests to run they rely on

functionality provided by the

acl and xattr Debian packages. Adding

those to the Build-Depends list in the debian/control file of the

rsync Debian package repo made them run.

- Four upstream tests required root privileges to run. The

autopkgtest

tool knows the needs-root restriction for that reason. However, Samuel

and I agreed that the tests should not exclusively run with root

privileges. So, instead of just adding the restiction to the existing

autopkgtest test, we created a new one which has the needs-root

restriction and runs the upstream-tests-as-root script - which is

nothing else than a symlink to the existing upstream-tests script.

The commits to implement these changes can be found in this merge

request.

The careful reader will have noticed that I only made 2 + 4 = 6 upstream

test cases run out of 7: The leftover upstream test is checking the

functionality of the --ctimes rsync option. In the context of Debian, the

problem is that the Linux kernel doesn’t have a syscall to set the creation

time of a file. As long as that is the case, this test will always be

skipped for the Debian package.

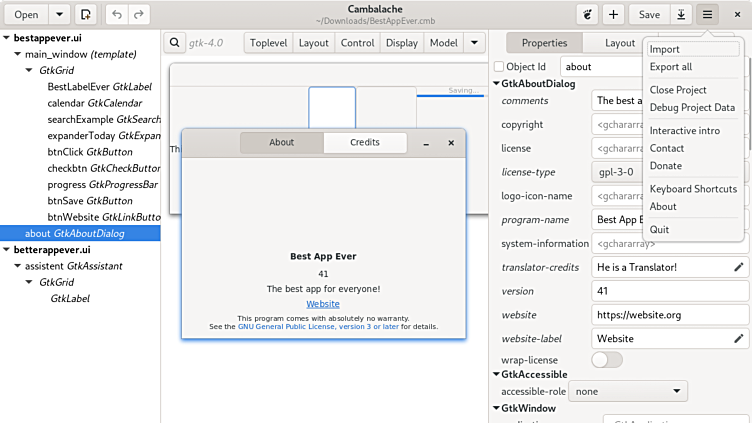

When it came to writing Debian specific test cases I started of a completely

clean slate. Which is a blessing and a curse at the same time: You have full

flexibility but also full responsibility.

There were a few things to consider at this point in time:

-

Which language to write the tests in?

The programming language I am most proficient in is Python. But testing a

CLI tool in Python would have been weird: it would have meant that I’d

have to make repeated subprocess calls to run rsync and then read from

the filesystem to get the file statistics I want to check.

Samuel suggested I stick with shell scripts and make use of diffoscope -

one of the main tools used and maintained by the Reproducible Builds

project - to check whether the file contents and

file metadata are as expected after rsync calls. Since I did not have

good reasons to use bash, I’ve decided to write the scripts to be POSIX

compliant.

-

How to avoid boilerplate? If one makes use of a testing framework, which

one?

Writing the tests would involve quite a bit of boilerplate, mostly related

to giving informative output on and during the test run, preparing the

file structure we want to run rsync on, and cleaning the files up after

the test has run. It would be very repetitive and in violation of DRY

to have the code for this appear in every test. Good testing frameworks

should provide convenience functions for these tasks. shunit2 comes with

those functions, is packaged for Debian, and given that it is already

being used in the curl project, I decided to go with it.

-

Do we use the same directory structure and files for every test or should

every test have an individual setup?

The tradeoff in this question being test isolation vs. idiosyncratic

code. If every test has its own setup, it takes a) more work to write the

test and b) more work to understand the differences between

tests. However, one can be sure that changes to the setup in one test will

have no side effects on other tests. In my opinion, this guarantee was

worth the additional effort in writing/reading the tests.

Having made these decisions, I simply started writing

tests… and ran into issues very quickly.

When testing the rsync --times option, I observed a weird phenomenon: If

the source and destination file have modification times which differ only in

the nanoseconds, an rsync --times call will not synchronize the

modification times. More details about this behavior and examples can be

found in the upstream issue I raised. In the Debian tests we

had to occasionally work around this by setting the timestamps explicitly

with touch -d.

In one test case, I was expecting a difference in the modification times but

diffoscope would not report a diff. After a good amount of time spent

on debugging the problem (my default, and usually correct, assumption is

that something about my code is seriously broken if I run into issues like

that), I was able to show that diffoscope only displayed this behavior in

the version in the unstable suite, not on Debian stable (which I am running

on my development machine).

Since everything pointed to a regression in the diffoscope project and

with diffoscope being written in Python, a language I am familiar with, I

wanted to spend some time investigating (and hopefully fixing) the problem.

Running git bisect on the diffoscope repo helped me in identifying the

commit which introduced the regression: The commit contained an optimization

via an early return for bit-by-bit identical files. Unfortunately, the early

return also caused an explicitly requested metadata comparison (which could

be different between the files) to be skipped.

With a nicely diagnosed issue like that, I was able to

go to a local hackerspace event, where people work on FOSS together for an

evening every month. In a group, we were able to first, write a test which

showcases the broken behavior in the latest diffoscope version, and

second, make a fix to the code such that the same test passes going

forward. All details can be found in this merge request.

At some point I had a few autopkgtests setup and passing, but adding a new

one would throw me totally inexplicable errors. After trying to isolate the

problem as much as possible, it turns out that shunit2 doesn’t play well

together we the -e shell option. The project mentions this in the release

notes for the 2.1.8 version, but in my opinion a

constraint this severe should be featured much more prominently, e.g. in the

README.

The centrepiece of this project; everything else has in a way only been

preparation for this.

Obviously, the goal was to reuse the previously written local tests in some

way. Not only because lazy me would have less work to do this way, but also

because of a reduced long-term maintenance burden of one rather than two

test sets.

As it turns out, it is actually possible to accomplish that: The

remote-tests script doesn’t do much apart from starting an ssh server on

localhost and running the local-tests script with the REMOTE environment

variable set.

The REMOTE environment variable changes the behavior of the local-tests

script in such a way that it prepends "$REMOTE": to the destination of the

rsync invocations. And given that we set REMOTE=rsync@localhost in the

remote-tests script, local-tests copies the files to the exact same

locations as before, just over ssh.

The implementational details for this can be found in this merge

request.

Most of my development work on the Debian rsync package took place during

the Debian freeze as the release of Debian Trixie is just

around the corner. This means that uploading by Debian Developers (DD) and

Debian Maintainers (DM) to the unstable suite is discouraged as it makes

migrating the packages to testing more difficult for the Debian release

team. If DDs/DMs want to have the package version in unstable migrated to

testing during the freeze they have to file an unblock request.

Samuel has done this twice (1, 2) for my work for Trixie but has

asked me to file the proposed-updates request for current

stable (i.e. Debian Bookworm) myself after I’ve backported my

tests to bookworm.

To run the upstream tests which check access control list and extended file

system attributes functionality, I’ve added the acl and xattr packages

to Build-Depends in debian/control. This, however, will only make the

packages available at build time: If Debian users install the rsync

package, the acl and xattr packages will not be installed alongside

it. For that, the dependencies would have to be added to Depends or

Suggests in debian/control. Depends is probably to strong of a relation

since rsync clearly works well in practice without, but adding them to

Suggests might be worthwhile. A decision on this would involve checking,

what happens if rsync is called with the relevant options on a host

machine which has those packages installed, but where the destination

machine lacks them.

Apart from the issue described above, the 15 tests I managed to write are

are a drop in the water in light of the infinitude of rsync

options and their combinations. Most glaringly, not all

options of the --archive option are covered separately (which would help

indicating what code path of rsync broke in a regression). To increase the

likelihood of catching regressions with the autopkgtests, the test

coverage should be extended in the future.

Generally, I am happy with my contributions to Debian over the course of my

small GSoC project: I’ve created an extensible, easy to understand, and

working autopkgtest setup for the Debian rsync package. There are two

things which bother me, however:

- In hindsight, I probably shouldn’t have gone with

shunit2 as a testing

framework. The fact that it behaves erratically with the -e flag is a

serious drawback for a shell testing framework: You really don’t want a

shell command to fail silently and the test to continue running.

- As alluded to in the previous section, I’m not particularly proud of the

number of tests I managed to write.

On the other hand, finding and fixing the regression in diffoscope - while

derailing me from the GSoC project itself - might have a redeeming quality.

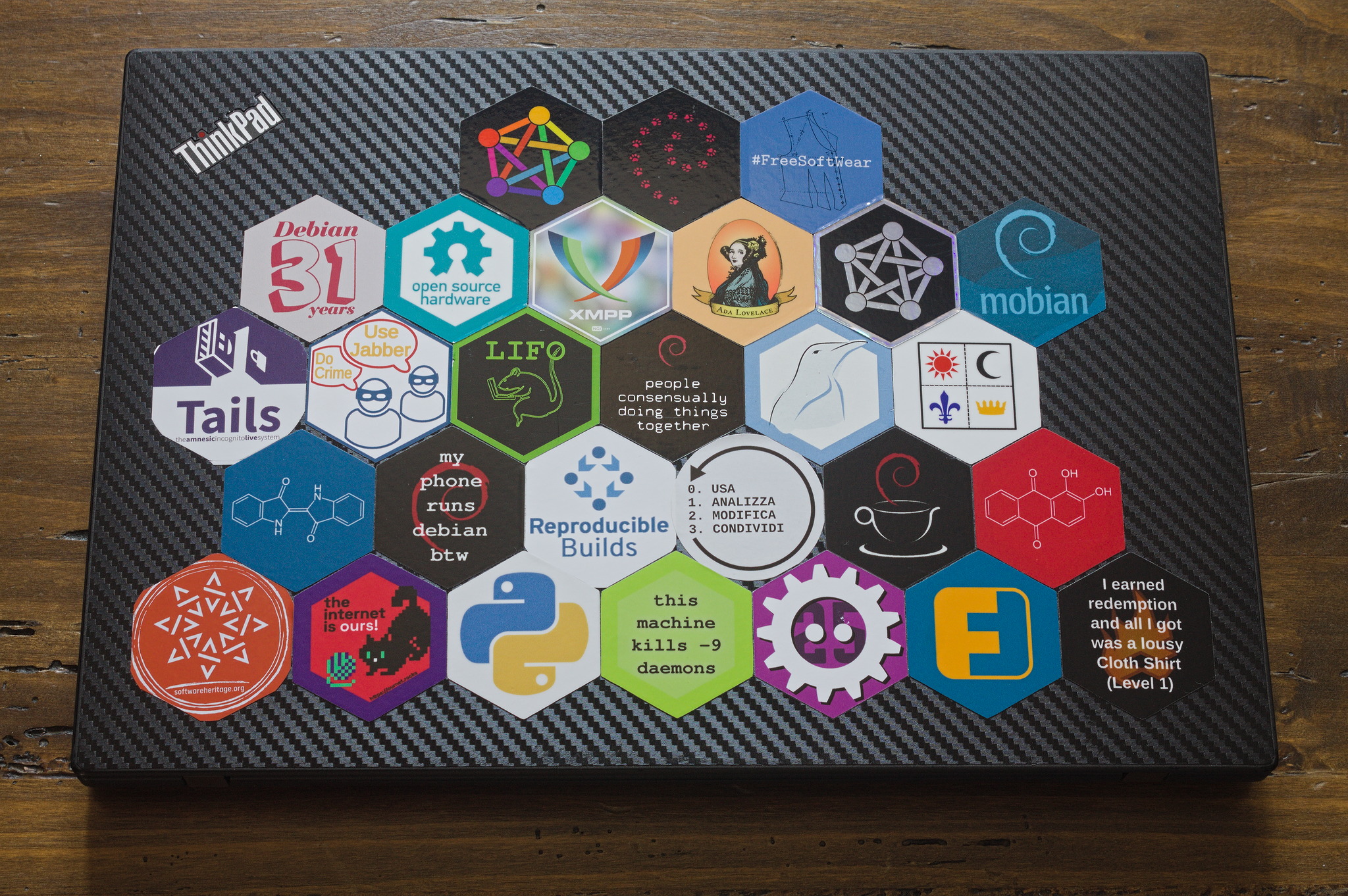

By sheer luck I happened to work on a GSoC project at Debian over a time

period during which the annual Debian conference would take place

close enough to my place of residence. Samuel pointed the

opportunity to attend DebConf out to me during the community bonding period

and since I could make time for the event in my schedule, I signed up.

DebConf was a great experience which - aside from gaining more knowledge

about Debian development - allowed me to meet the actual people usually

hidden behind email adresses and IRC nicks. I can wholeheartedly recommend

attending a DebConf to every interested Debian user!

For those who have missed this year’s iteration of the conference, I can

recommend the following recorded talks:

While not featuring as a keynote speaker (understandably so as the newcomer

to Debian community that I am), I could still contribute a bit to the

conference program.

The Debian Outreach team has scheduled a

session in which all GSoC and Outreachy students

over the past year had the chance to present their work in a lightning talk.

The session has been recorded and is available online, just

like my slides and the source for them.

Additionally, with so many Debian experts gathering in one place while KDE’s

End of 10 campaign is ongoing, I felt it natural to

organize a Debian install workhop. In hindsight I can say

that I underestimated how much work it would be, especially for me who does

not speak a word of French. But although the turnout of people who wanted us

to install Linux on their machines was disappointingly low, it was still

worth it: Not only because the material in the repo can be

helpful to others planning install workshops but also because it was nice to

meet a) the person behind the Debian installer images and b) the

local Brest/Finistère Linux user group as well as the motivated and helpful

people at Infini.

I want to thank the Open Source team at Google for organizing GSoC: The

highly structured program with a one-to-one mentorship is a great avenue to

start contributing to well established and at times intimidating FOSS

projects. And as much as I disagree with Google’s surveillance

capitalist business model, I have to give it to them that the company at

least takes its responsibility for FOSS (somewhat) seriously - unlike many

other businesses which rely on FOSS and choose to freeride of it.

Big thanks to the Debian community! I’ve experienced nothing but

friendliness in my interactions with the community.

And lastly, the biggest thanks to my GSoC mentor Samuel Henrique. He has

dealt patiently and competently with all my stupid newbie questions. His

support enabled me to make - albeit small - contributions to Debian. It has

been a pleasure to work with him during GSoC and I’m looking forward to

working together with him in the future.

There's a lovely device called a

There's a lovely device called a  Partners holding big jigsaw puzzle pieces flat vector illustration. Successful partnership, communication and collaboration metaphor. Teamwork and business cooperation concept.

Partners holding big jigsaw puzzle pieces flat vector illustration. Successful partnership, communication and collaboration metaphor. Teamwork and business cooperation concept.

What a surprise it's August already.

What a surprise it's August already.

Pollito and the gang of DebConf mascots wearing their conference badges (photo: Christoph Berg)

Pollito and the gang of DebConf mascots wearing their conference badges (photo: Christoph Berg) F/DF7CB in Brest (photo: Evangelos Ribeiro Tzaras)

F/DF7CB in Brest (photo: Evangelos Ribeiro Tzaras)

The northern coast of Ushant (photo: Christoph Berg)

The northern coast of Ushant (photo: Christoph Berg)

Having a nice day (photo: Christoph Berg)

Having a nice day (photo: Christoph Berg)

Pollito on stage (photo: Christoph Berg)

Pollito on stage (photo: Christoph Berg)